Jessica Sylvia had a lot to look forward to this year. A transgender incarcerated person and advocate at Monroe Correctional Complex in Washington state, she was excited about the sociology classes she was taking for her bachelor’s degree. Her mother was coming for a visit in the spring. And she’d finally gotten scheduled for an evaluation for gender-affirming surgery, something she’s wanted for 27 years.

Then COVID-19 happened, and everything was canceled.

Now, Sylvia’s more afraid of the impact of prolonged isolation than of contracting coronavirus. “I’m feeling disconnected. I’m feeling higher levels of depression and anxiety,” she said. “And I don’t feel that there’s anyone to listen to me or understand my needs.”

LGBTQ people, especially those who are low-income and from communities of color, are incarcerated at a disproportionately high rate. They’re also more vulnerable to sexual and physical violence, and mistreatment.

Sylvia said she regularly experiences transphobia: Her birth certificate was legally changed to reflect her female gender, yet she is housed at a male facility and said corrections officers call her by her birth name. It took her nearly 11 months to get permission to wear barrettes. She spends most of her time, COVID-19 or not, by herself. Department of Corrections communications director Janelle Guthrie did not respond to any of Sylvia’s direct claims, but did point to an updated policy on treatment of transgender prisoners.

Around the country, COVID-19 cases are rising in prisons and jails as incarcerated people continue to have little outside contact. “A worry that’s widespread among all sorts of organizations is that less access to the facility means less oversight and accountability,” said Biff Chaplow, director of the Portland-based organization Beyond These Walls.

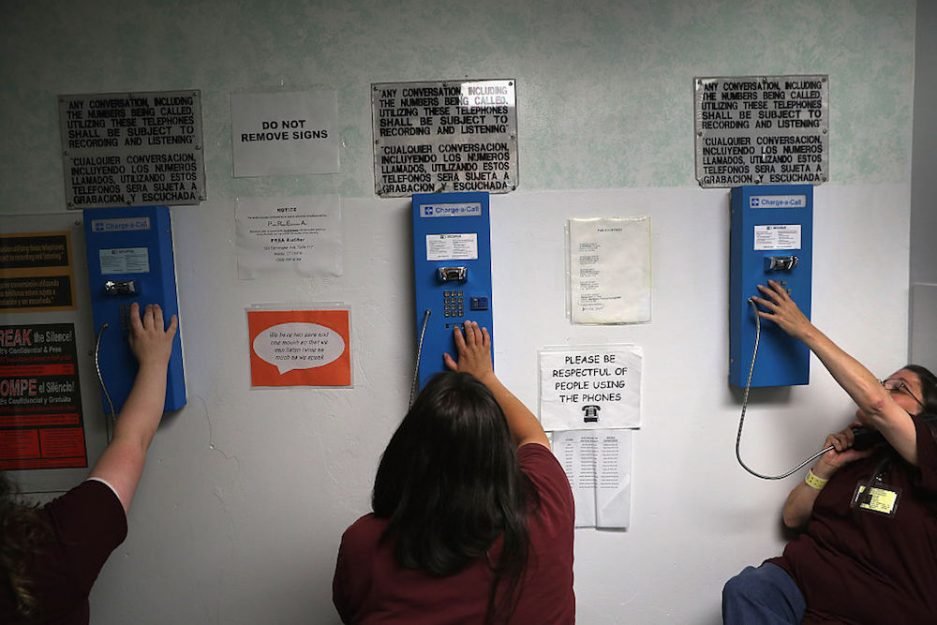

The organization connects LGBTQ incarcerated people in Oregon and Washington with pen pals and facilitates programs like the Transgender Leadership Academy, believing “there’s a Marsha P. Johnson sitting in prison right now.” When they paused their programming at three facilities, Chaplow immediately pivoted to create a prepaid crisis line. The goal is to provide emotional support to incarcerated people in the Pacific Northwest no matter how they identify, and to advocate for them. Every two weeks Chaplow sends a report to a coalition of partner organizations, including ACLU of Oregon, working to keep incarcerated people safe.